A TREASURE IN RENNES-LE-CHÂTEAU HYPOTHESIS

The excellent French researcher Patrick Mensior published the Journal of Abbé Saunière 1901-1905 in 2017. He painstakingly transcribes every diary entry and provides notes on who all the people were that he mentions as well as the sights and places of interest.

At the end of the book Mensior gathers together all the information and discusses his own theory about what was going on.

Here below I have translated some of it for interested readers. To order the book see the link HERE.

During my investigations, I was able to learn from several witnesses that one day in 1905 the Abbé Saunière had returned to his village, from a place where he went regularly, completely muddy from head to toe and superficially wounded. Seeing him in this state, Marie, taking off his bag, hastened to clean the priest and bandage a few of the scratches.

Where had he come from?

The answer is probably the one given on pages 271 and 272 of L'Héritage de l'abbé Saunière by Claire Corbu and Antoine Captier (Ed. (Eil du Sphinx 2012): "The abbe went to the vault on certain nights, in a small room arranged towards the middle of the underground where this treasure was stored. He returned from there just before dawn, often soaked and full of mud, with his booty which he carried in a large haversack which Marie had made for him".

What did he bring back from these nocturnal trips?

"... what he brought back was mainly objects of worship such as ciboriums or reliquaries but also jewelry, old gold coins, small porcelain objects, large books with brown leather bindings and sometimes even small furniture".

The Captier's add:

“This merry-go-round lasted several years and only stopped towards the end of the work on the estate. What had happened? We learned that, following torrential rains, there had been a landslide in the underground area which prohibited access to the treasure room. With the help of Marie and the faithful Augustou, the priest tried, but in vain, to shore up the crumbling part. But he quickly had to give it up because the underground was constantly sinking, threatening to bury them. Marie, who was superstitious, was convinced that this landslide was a warning from Heaven and that you should never try to enter it again or reveal its location to anyone".

It was probably this episode which, years later, inspired Marie Dénarnaud, when she was discussing with one of her friends, Mme Vidal, the following response: "With what the priest left, we would feed all of Rennes for a hundred years and there would still be some left!" To which her friend then asked her in astonishment: "But since he left you so much money, why do you live like a poor person?" Mary closes this point of the discussion with this sentence: “A aquo ni tusti pas! » which can be translated as « I don't touch that! »

The abbe was therefore in this treasure room underground and was caught out during a landslide which occurred due to the precipitations of heavy rain and snow that the region had been experiencing for some time. By combining two documents of different sources, it is now possible to situate this climatic event in time. It was Saturday 4 and Sunday, March 5, 1905, and Abbé Saunière wrote the following in his personal diary:

Saturday March 4. excessively bad day; the worst of the year, great snowstorm. Oscar cannot work from the cold. He leaves at 3 a.m. but frightened by the sight of the amount of snow, he returned to Rennes completely upset. Am sick. Cold and pain on the right side. Awful night of very bad weather. Lots of snow.

Sunday March 5. Very bad day. Because of my illness, I do not say mass and stay all day in it. We still have Oscar who is panic-stricken with fear.

A few days later, on March 10, 1905, the Municipal Council of Rennes-le-Château met for an extraordinary session following urgent work carried out at its request by a worker from Couiza on the rural road linking the village to Capia where a few days before, a landslide had caused serious damage:

"M. le Marie asks the Council that, following a landslide on the rural road from Rennes-le-Château to Capia, mine and clearing work was immediately necessary; that these works were carried out by Ahonménat Sébastia, a Spanish subject domiciled in Couiza, who requests immediate payment, as per his memorandum to the sum of sixty-six francs".

Here, the municipal says that the damaged part concerns the path that connects the village to the farmhouse of Capia.

In 2008, after a discussion with the Captiers, they confirmed to me that a person of whom they were in relation, and who lived at the estate at the time of Noël Corbu, had told them that according to Marie, from the place where the parish priest went silently, one could see the walls of the castle. Captier recorded this testimony on page 272 of his book of 2012 already quoted.

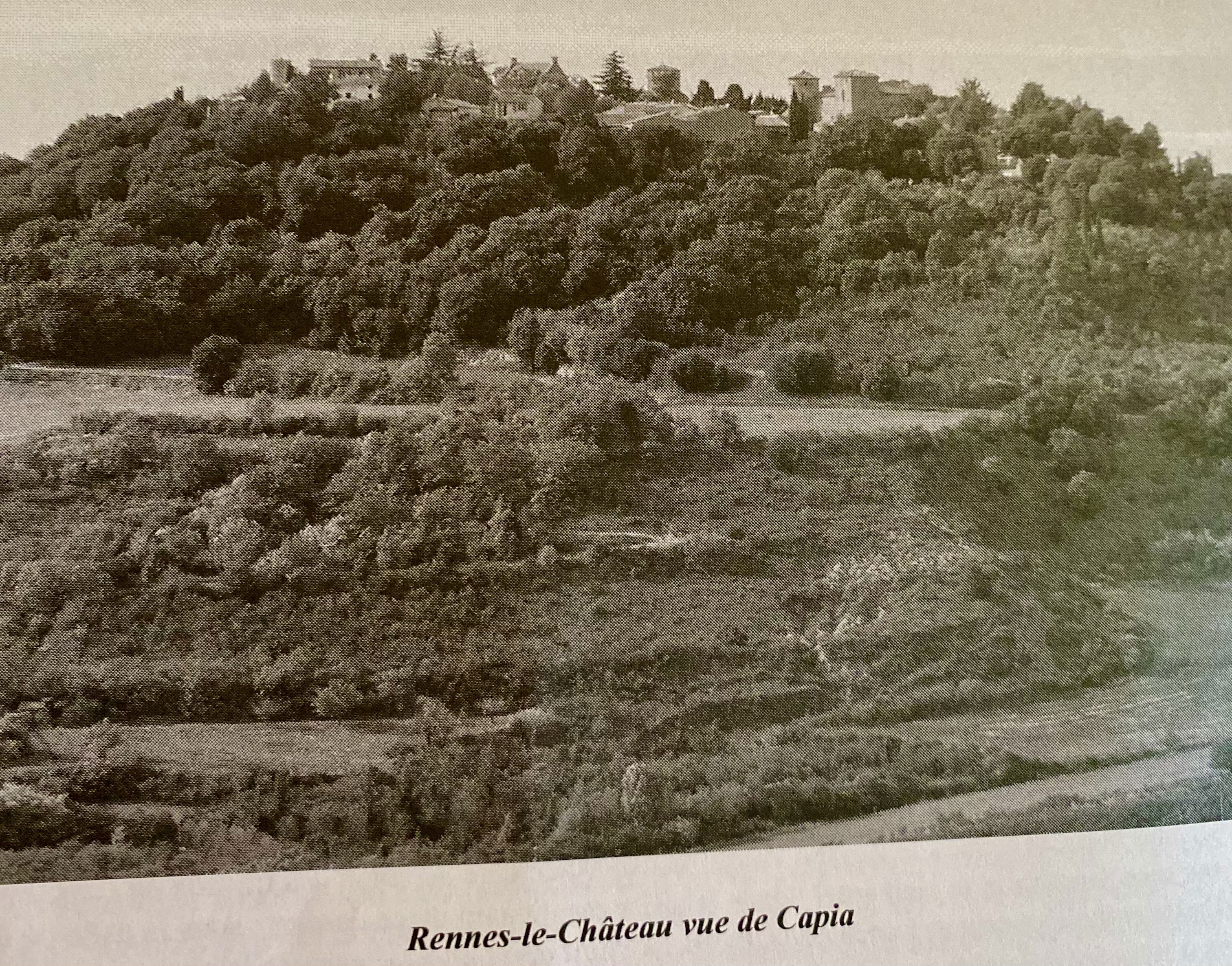

If we examine the various cadastral documents at our disposal, in particular the one reproduced before, at first glance, it seems that the castle is not visible in the foreground since it is behind several constructions! But once there, in Capia, we can see that the different reliefs of the land make it possible this time to clearly distinguish the walls of the castle which have almost passed in the foreground!

Rennes-le-Château seen from Capla

An underground in which one could go on horseback!

Antoine Captier also reports the following testimony:

"According to the former mayor of Couiza, Mr. Faure today deceased, whose family lived on the Carla farm in the time of the Abbé Saunière, and other people who confirmed it to me afterwards, when they retraced the route, they found an underground passage of which we can still see traces".

He places it where the road from Rennes-le-Château to Capia was redone - it is located precisely at its intersection with the black line fault on any map of the area.

What was the origin of this treasure?

Testimonies brought back to us tell that Bérenger Saunière had the opportunity to make more discoveries in various caches of the Sainte Marie-Madeleine church during the repair work: for example the wall of the old Sacristy and the old altar; in the Carolingian pillar of the latter; under the stone slab of Choir, in the wooden baluster supporting the old pulpit; when dismantling old paneling; and in the bell tower constituting what may be called a hoard. Apart from possible relics in the altar, this hoard was made up of old pieces, which he passed off as medals from Lourdes to the curious, objects of worship and probably also some documents concerning the consecration of the Church. Most of these deposits had been organized, a century before Abbé Saunière, by one of his predecessors Antoine Bigou, who had to leave Rennes-le-Château in 1792 to flee the revolutionary turmoil.

But were books in these repositories! We know, having found a substantial part of it, that many works from Saunière's library, in which he had notably inserted his Ex-Libris, had been published in the 17th and 18th centuries. Could it be, therefore, that these books were taken by Abbé Saunière from the treasure room of Bigou for his own personal library?

After the publication by Jules Doinel, in 1899, of the inventory drawn up in 1792 of the furniture and ecclesiastical effects of the bishopric of Alet in particular those living with Lacropte, Gaston Jourdanne is among historians who were surprised by the few documents found at the bishopric after the Bishop left Alet for exile in Spain in order to flee the French Revolution: "The Episcopal Library amounted to several volumes, that is to say scarcely only a few scattered pounds, of the time of Mgr de Bocaud, in the bedroom and the billiard room! What happened to the rest? he wonders!

It seems obvious that Mgr de la Cropte de Chantérac could not encumber himself with a large volume of miscellaneous furniture and other items during his exile.

Still according to Gaston Jourdanne, a fine bibliophile: M. de Chanterac had the necessary facilities to conceal most of his household effects and especially the fine collection he inherited from his predecessor. Unfortunately, for bibliophiles, there is no indicative sign to enable them to recognize, from time to time, a vestige of the library of the last two mentioned Bishops of Alet".

It is probably because Bishop de Chantérac took the necessary time to organize his visit to Spain that a number of effects could not be identified during the inventory started on October 9, 1792. This is also the opinion of Gaston Jourdanne:

“The conduct of the authorities of the District does not appear to have been very severe viz a viz their former bishop”.

Other treasure items...

Several pieces of the treasure have remained today in the families of the people who received them from Abbé Saunière or from Marie Dénarnaud. One of the best known of these testimonies is that of the old butcher of Quillan who had a very old bracelet offered by the priest. One of Marie Dénarnaud's foster sisters also own several jewels given by the latter. Another lady had received from the priest for her communion, a gold jewel encrusted with rubies and emeralds. A researcher who wrote recently on his website said that one of his relations in Campagne-sur-Aude had shown him a Gallic gold torque as well as small ingots of the same metal from the treasure of Abbé Saunière. The Captiers also say that: in the time of the priest, Marie Dénarnaud wore very beautiful antique jewels which she stopped wearing when he began to have trouble with the bishopric”. A specialist would have confided to Antoine Captier that the support of the little Jesus of Prague in his possession dates from the 16th century. During his trials, Abbé Saunière wrote in his defence in a letter of November 25, 1911 to the Officials that he traded in old furniture : “The old furniture, earthenware and fabrics are the result of my travels in the country. The sale compensates me for my research and my shopping”. Among the furniture he put in the villa was a Louis XIIIth armchair, probably from the former bishopric. To this exhaustive inventory, we can add relics, all kinds of religious objects (chalices, ciboria, rosaries, crosses and probably other ancient jewellery).

Moreover, during my readings I have sometimes come across references given by authors referring to documents from the diocese of Alet, in particular minutes and pastoral ordinances. To find out about these, I questioned both the departmental archives of Aude and the Bishop of Carcassonne. Together, it was then explained to me that very few of the documents had been preserved from the diocese of Alet'. Where had these diocesan archives gone?

As Gaston Jourdanne thinks, Mgr de Chantérac took the time to prepare his exile, and in particular to preserve both the property of the bishopric as well as his own in the hope of a possible return after the Revolution had passed. But long before this exile, on February 13, 1790, the Constituent Assembly suppressed religious orders and placed the property of the clergy at the disposal of the State. Several oaths will be ordered following these measures to the religious until that of August 25, 1792. It is by proxy and by an act of the notary Prax that Bishop Chantérac takes this oath at the common house of Alet: he is presiding to sieur Jacques François Dellac, Surgeon of this city, the founded prosecutor of sieur Lacropte Chantérac of the former diocese of Alet by an act of August 21 of the present year, registered in Limoux the following day same year signed by Blanque, which says sieur Dellac would have said that sieur Lacropte Chantérac being at home due to illness, and not being able to go to the Maison Commune to take the civic oath ordered by the law of 11 of the current 1792 to the Municipality : would have given him his declaration in which the said oath is expressed. Reading made both of the act of proxy in favour of the said Mr. P and of the declaration of the said Mr. Lacropte Chantérac, the Assembly truly satisfied with the patriotism that the said Lacropte Chantérac, bishop of the former diocese, manifests on this day; flattering himself that the example of devotion he gives to public affairs will be able to carry great weight and bring back a large number of refractory law, attesting to the surplus that he has not submitted any substantive complaint to date, proving that the small disturbances which have sometimes agitated this commune having been caused by the different opinions of the said sieur Lacropte”. A month after having taken the following oath, Bishop de Chantérac left Alet and swore to maintain freedom and equality or to die defending it. Which I declare sworn”.

After his departure into exile, the district of Limoux draws up the list of priests deported or left in execution of 26 August 1792 relating to the deportation of unsworn priests and generally of all those who are deemed shortly after words. This is the case of Bishop de Chantérac and Father Antoine Bigou.

Antoine Bigou former parish priest of Rennes / His property sequestered and put up for sale - Lacropte bishop of Alet / His belongings sold, has no assets

If the bishop of Alet does not own any property, the inventory drawn up on October 9, 1792 also does not attribute to him any valuable objects, neither in precious metal, nor artistic, religious or historical!

All these arbitrary and demeaning measures taken by the authorities against the religious are so many indicators contributing to consider their escape which they will organize methodically and conscientiously. This is how the bishop decides to shelter everything that is precious to the bishopric and for himself in order to preserve it from the Revolution and in the hope, once it is over, of finding it.

At this time, several possibilities arise - the bishop and the abbe Bigou know of the existence in the countryside of Rennes-le-Château of an old underground passage/grotte perhaps from the time of the Voisins family, which can be reused as a cache, after having made arrangements to conceal the property of the bishopric of Alet and the bishop. Or, the cache is created in a chosen place not far from Rennes-le-Château and its location known only to them and perhaps to a few religious close to their bishop. Once this cache is operational, the objects are methodically deposited there. One can imagine several nocturnal convoys of heavily laden mules departing from Alet and discreetly going up the mountain to the converted cache of Rennes-le-Château only about ten kilometers away. Once the treasure is safe and the cache closed, Bishop de Chantérac takes the road to exile to reach Sabadell in Spain, Antoine Bigou, who left before him, that of Quillan at first where there is his family and then on to Collioure. But it turns out that the protagonists sharing the secret of the treasure's location die out one by one before the end of the Revolution. Among them, beyond the bishop, we can cite his sister Elizabeth, Father Antoine Bigou and his sister Gabrielle. Of these four, probably the few rare religious close to the bishop are also in the confidence! Bishop Charles de la Cropte de Chantérac died in Sabadell on April 27, 1793, his sister Elizabeth Françoise de la Cropte de Chantérac, young lady of Beauvais, died in Alet January 1797), her remains lie in the Saint-André d'Alet cemetery; Antoine Bigou died in Collioure, during the Spanish period, on March 20, 1794: his sister Gabrielle died in Sournia on 21 Ventôse, Year VIII (March 12, 1800). This is how the treasure of Alet gets lost. It will be rediscovered a century later by the Abbé Saunière thanks to indications found during work in the church. Before his exile, Antoine Bigou had hidden there one or more documents, probably in Latin, allowing, by indications, to open the way to the cache of the treasure of Alet.

Another treasure?

Mgr de Chantérac is not the only one to have concealed a treasure during this troubled time. Very close to Alet, in Pieusse, which at that time depended on the diocese of Narbonne, the owner of the castle, Archbishop Mgr Richard DiIlon, did the same by hiding an important treasure in an underground passage, that of Narbonne, before being exiled to Koblenz then to England where he died on July 5, 1806. On March 16, 2007, his remains were transferred to a vault in the Saint-Martin chapel of Narbonne cathedral. Two documents preserved in the departmental archives in Toulouse attest to the presence of the treasure of Narbonne in one of the underground passages of the château de Pieusse: one of the signatories of the first document attests to the following: "having deposited in the underground passage of the Pieusse manor the sum of four hundred and seven set in gold worth five hundred and nine pounds, each set for the coachman at war who is in the country”. The second reveals the following: “Fortune lies under the castle six fathoms in. There is a large lausse that hides the small colidor that goes to the bottom of the underground. There is an iron door; when we have opened the door, there is a large slab where there is the treasure. There are 13 sets of these gold louis d'or de 100 livres de 20 sou a then 19 pugnères de 6 francs, which makes set thousand livres and then all the genterie of the castle and then crosses d'or ambé de diamans and sabers which have the handle in silver armed with precious stones which all together are worth four million pounds .."

The parchment ends like this.

Where is the treasure of Alet?

According to the testimonies and the documents, the treasure would be in the large cavity where the landslide took place and was reported in 1905. It is likely that this land was not the property of Abbé Antoine Bigou or Mgr de Chantérac but more probably that of a third party: the sister of the parish priest or that of the bishop, for example. We know in particular that Gabrielle Bigou lodged complaints with the State because among the goods identified by the parish priest in the 1793 inventories drawn up by the municipal officers and the surveyor, there were some that had been taxed when they were her only property of which she had left the enjoyment to her brother.

The holders of Abbé Saunière's secret!

After he decided in 1905 to permanently close the treasure cache, those who still share his secret were very few: Marie Dénarnaud, Auguste Fons, perhaps his wife Julie Maleville, but also the Espéraza priest, the abbe Riviere. When, in January 1917, he arrived at the presbytery of Rennes-le-Château to receive a confession from his colleague at the gates of death, he was far from suspecting what he was going to hear. Sauniere first tells him that for ages he has used the money from the thousands of Mass intentions he has from donors to finance the repairs to the church and the construction of his luxurious estate. Then, he discovered the treasure of Alet which did not belong to him but which he had drawn freely for years. But the most painful thing for the troubled confessor is to realize afterwards that he has always kept these confidences secret! Jean Fourié d'Espéraza and former president of the Academy of Arts and Sciences of Carcassonne, said to me during a discussion on Jean Rivière:

"His disorder on the occasion of the death of Saunière was the subject of various comments and, personally, I have always heard about it. It is even said that his death was partly due to the grief and disappointment he would have experienced on this occasion - what is it exactly? One fact is certain, according to those who knew him, Abbé Rivière was no longer the samee after the death of his colleague from Rennes-le-Château"