The crypt under the church of Rennes-le-Château

On August 26, 2011, the city council of Rennes-le-Château came out with extremely surprising and important news: it was decided that the experienced Belgian architect Paul Saussez, who has been researching the history of Rennes-le-Château and the local church for more than 15 years, was to be appointed to prepare a permit and file to carry out archaeological excavations in the village church of Rennes-le-Château. Pending the undoubtedly important finds of Paul Saussez, it is interesting to shed light on our knowledge of the crypt thought to be under the church.

There are several indications that the origin of Saunière's inexplicable wealth can be traced back to a discovery in the crypt in the church of Rennes-le-Château. The crypt does exist and on the basis of evidence this will be demonstrated here. But first let's shed light on what exactly a crypt is.

What is a crypt?

The word crypt comes from the Greek word krúptein which means 'to hide'. During the first centuries of our era, peaceful Christians, who had been persecuted and killed by the Romans, were buried in underground hidden catacombs, out of sight of the ruler. Later, churches were built on these hidden cemeteries to honour the martyrs and from there the idea of the crypt grew.

An example of a catacomb in Rome (Photo © http://jongerlo.org)

In the contemporary Christian world, the word crypt is used to refer to a tomb under a church that contains relics or tombs. Usually the crypt was located under the apse of the church, just below the altar. In later times, in addition to the crypt, the graves of clergy, nobles or their blood relatives were also housed. As will be read later in this article, there are two types of burial spaces under the church of Rennes-le-Château, which we will often both designate with the umbrella term 'crypt'.

Conditions for a crypt

In the 2010 edition Parle-moi de Rennes-le-Château, French researcher Patrick Mensior came out with an interesting article. This was an extract from a 19th-century French ecclesiastical code that discussed the conditions for the construction, furniture and decoration of churches according to the canonical laws (Mensior 2010). In the church book, a separate chapter was also devoted to the conditions for a crypt in a church. Article 2 in particular is interesting to us and also very explicit:

| Regularly, a crypt has no reason to be if it does not contain the tomb of a saint. You must never do anything useless in a church. |

Translated into Dutch, this means that according to ecclesiastical law, there can only be a crypt in a church if there is a grave of a saint. Possibly this statement should also be extended to all kinds of religious objects. In addition, a crypt aims to bring the faithful as close as possible to the body of the saint, so that they can pray in silence here (Mensior 2010).

An example of a relic from Saint-Hilaire Abbey; a forearm of a saint. (Photo © Beauseant 2010)

If the church of Rennes-le-Château has a crypt, this means that a saint has been buried. The key question is, of course: "Which saint?" Knowing that Saunière received many mass intentions from congregations from the most important Catholic sanctuary of France, namely Lourdes, this can only be an important saint.

We are not going to speculate here about what exactly may be in the crypt, because that is not the purpose of this article. So let's take a look at the hard evidence for the existence of a crypt in the church of Rennes-le-Château.

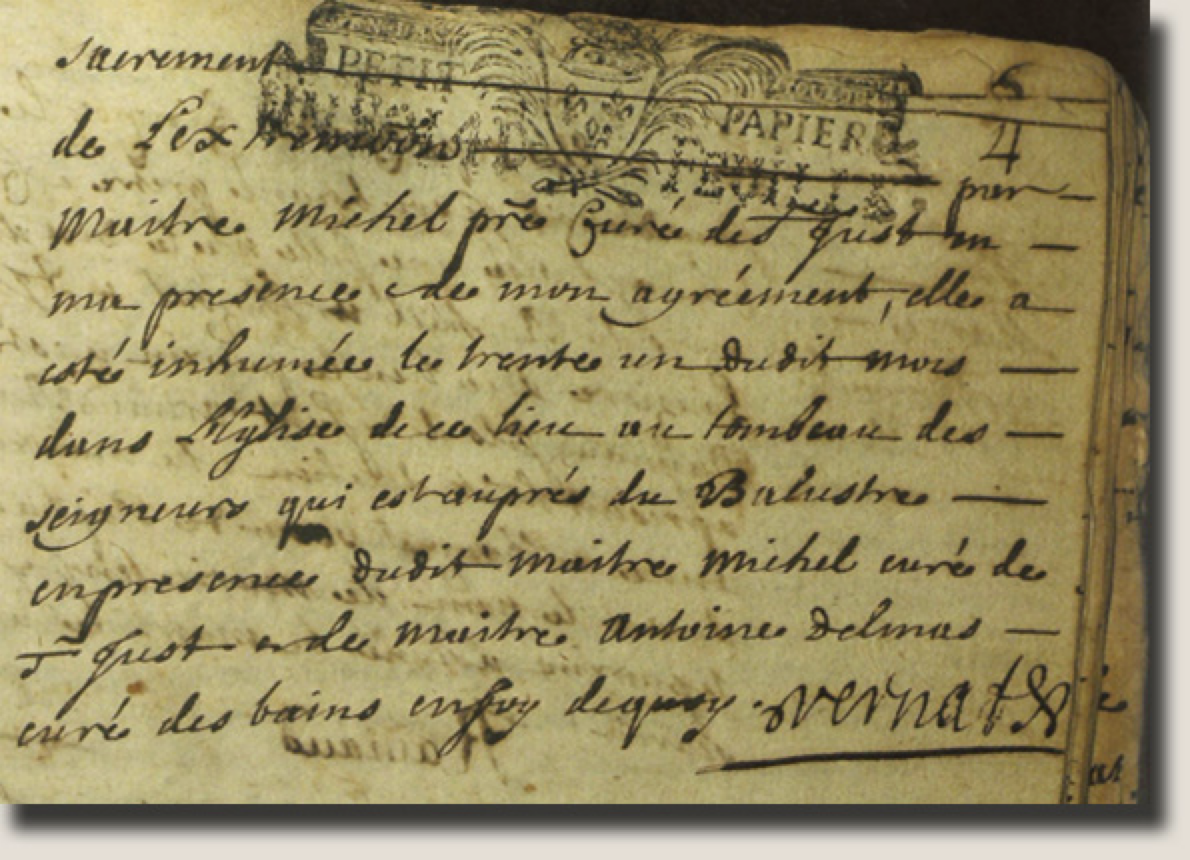

The old church register from 1694

In their excellent book L'Héritage de l'abbé Saunière, the couple Antoine Captier and Claire Corbu describe how they came into possession of Saunière's personal papers thanks to their father/father-in-law Noël Corbu and through the inheritance of Marie Dénarnaud. Between the paper's [of these] inheritance files of Saunière the couple Captier-Corbu [found] an old church register from 1694, which was mainly filled in by pastor Vernat, one of Saunière's pastors. Recently, Captier & Corbu have given away the church register and it is currently in the hands of the municipal administration of Rennes-le-Château. The following passage makes it clear why Saunière cherished the old church register so much between his personal possessions:

The old church register from 1694 with the infamous passage over the Tombeau des Seigneurs (Photo © Jean-Luc Robin 2005)

| "L'an mil sept cents cinq le trente jour de mars est décédée, dans le château de ce lieu, dame Anne Delsol, age d'about septante cinq ans, veuve de messire Marc Antoine Dupuy, sieur de Pauligne, ancien trésorier de France de la généralité de Montpellier... elle a été inhumée le trente et un du dit mois, dans l'église de ce place, au tombeau des Seigneurs qui est auprès du Balustre... "In the year 1705 died on the thirtieth day of the month of March in the castle of this village, Mrs. Anne Delsol, at about the age of 75, widow of Mr. Marc Antoine Dupuy, Lord of Pauligne, former thesaurian of the Montpellier region... she was buried on the thirty-first day of this month, in the church of this place, in the tomb of the Nobiles which is located near the Baluster..." (Captier & Corbu 1985: 271) |

This comment by pastor Vernat clearly proves that the local nobles were buried after their death in a burial room under the church, the Tombeau des Seigneurs as the crypt was called. The location of this crypt is even explicitly mentioned by Vernat, namely qui auprès du Balustre.

Access to the crypt next to the 'Balustre'

There is some doubt about the interpretation of the word 'Balustre', because according to several researchers, two places are possible. According to the Captier-Corbu couple, the word 'Balustre' refers to the wooden pillar that once supported the old wooden pulpit. Not illogical because this wooden pillar is already shrouded in mysteries due to its history; it was during Saunière's restoration and demolition work in 1887 that Antoine Captier's great-grandfather had found a glass phial containing a parchment in a secret cavity of this pillar. According to the Captiers, access to the crypt should therefore be found somewhere around the area of the old pulpit (Captier & Corbu 1985).

However, the Belgian architect and Rennes-le-Château researcher Paul Saussez has a different opinion. Based on old dictionaries from the time of Vernat, he concluded that the word 'Balustre' stood for a 'communion bank', also called 'balustrade'. Since the pulpit and the communion bench were in fact about close to each other, one of the entrances to the Tombeau des Seigneurs must be sought there.

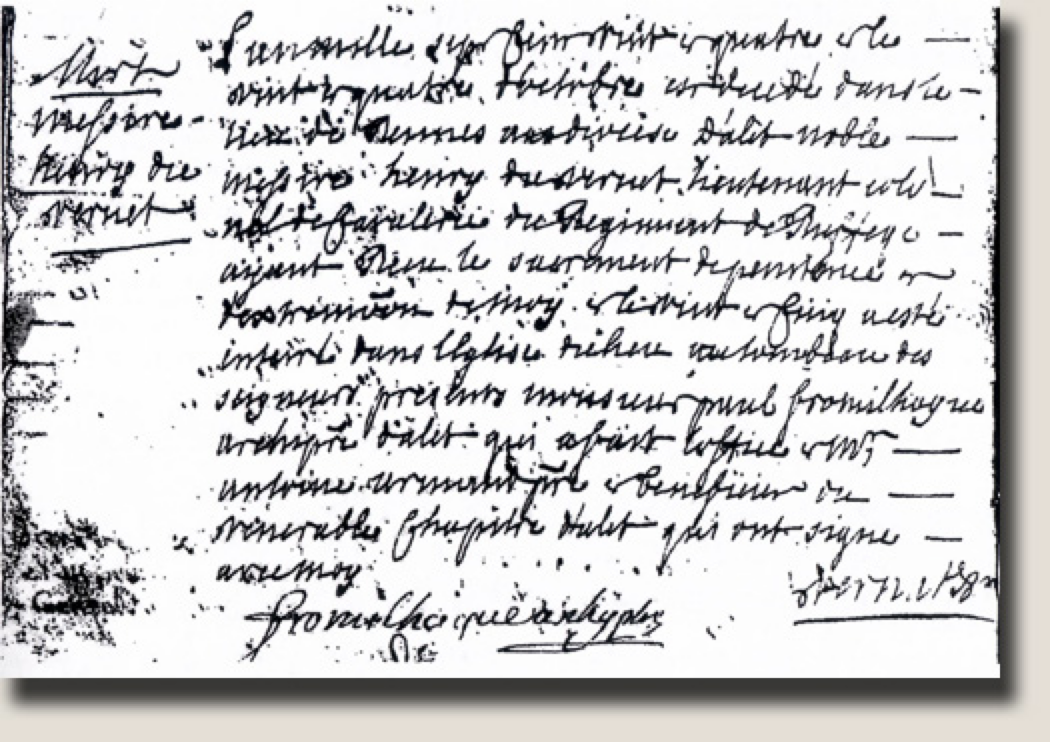

Crypt sealed between 1724-1739

"If there was indeed a crypt present in the church, why was the noble lady Marie de Nègre d'Hautpoul de Blanchefort buried outside in the public cemetery around the church?" is a question that many will ask themselves. The nobility was probably buried in the cemetery in later times because there was simply no more room in the crypt. It is possible for this reason that the crypt was closed. The old church registers may be able to shed light on the time when the crypt was closed. Through the church register of 1694, maintained by pastor Vernat, we know that in addition to the lady Anne Delsol, two other nobles were associated with the crypt. The last one mentioned is a certain Henry du Vernet. He died in 1724 and was also buried in the crypt (Mensior 2010).

Mention of the burial of Henry du Vernet in the Tombeau des Seigneurs (Photo © Mensior 2010).

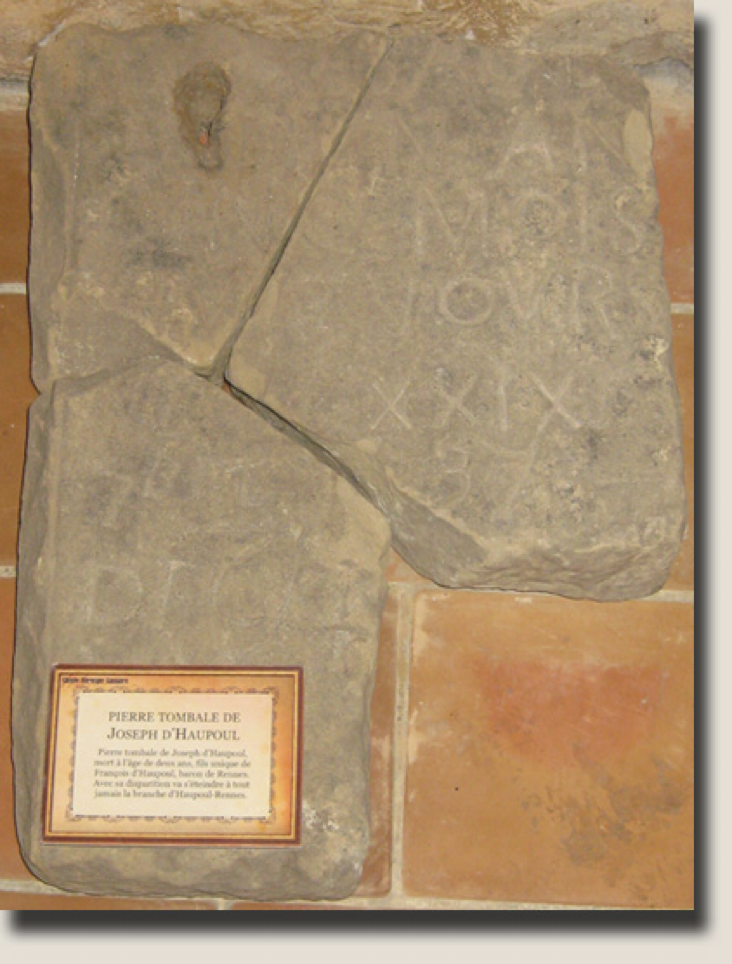

The church register of Vernat stops in 1725, the year in which the priesthood of Vernat in Rennes-le-Château came to an end. The next known church register does not begin until the year 1736. In other words, there is a gap of eleven years (Mensior 2010). In the next register from 1736 we learn that the next dead nobleman, which we know of, was Joseph d'Haupoul. The only son of François d'Haupoul and Marie de Nègre was only two years old. The church register explicitly states that Joseph was buried in the cemetery (Mensior 2010).

Paul Saussez suspects that the sealing of the crypt may also be to do with the death of Joseph d'Haupoul. He was the last male scion of the Hautpoul family branch from Rennes and with his death the Tombeau des Seigneurs had no more reasons for existence (Saussez 2011).

The tombstone of Joseph d'Haupoul, who died only two years old. (Photo © Beauseant 2011).

Through the church registers, we can therefore not help but note that access to the Tombeau des Seigneurs was closed sometime between 1724, the year Henry du Vernet was buried in the burial vault, and in 1739 when Joseph d'Haupoul was buried in the cemetery of Rennes-le-Château (Mensior 2010). In that fifteen-year period between 1724 and 1739, Rennes-le-Château had many priests. In 1725, Pastor Vernat ended his priesthood in Rennes-le-Château and until the appointment of Jean Bigou (the uncle of Antoine Bigou and later priest of Rennes-le-Château) in 1736, the ecclesiastical affairs in Rennes-le-Château were handled by the Capuchin brothers. Other sources mention that pastor Verger was Jean Bigou's predecessor. However, it is still unclear to determine which of all these clergy had the entrances to the crypt closed.

Rediscovery by Saunière

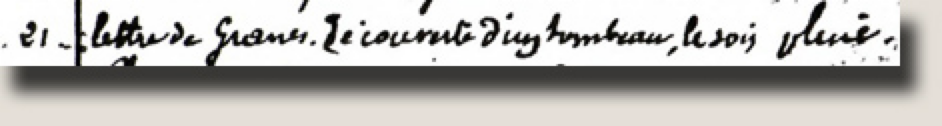

There is no doubt that Saunière rediscovered access to the crypt in 1891 during his restoration work. His diary of September 1891 containing the fragment 'Découverte d'un tombeau' speaks volumes about this.

Discovery of a tomb, Discovery of a grave, dated September 21, 1891. (Photo © Corbu & Captier 1985).

Thanks to his notebooks, in which Saunière carefully noted the workers' salaries, we know that on that day he had his workers prepare the installation work of the new pulpit. So it is near the old sermon choir and the 'Balustre' where a possible access staircase to the crypt probably begins.

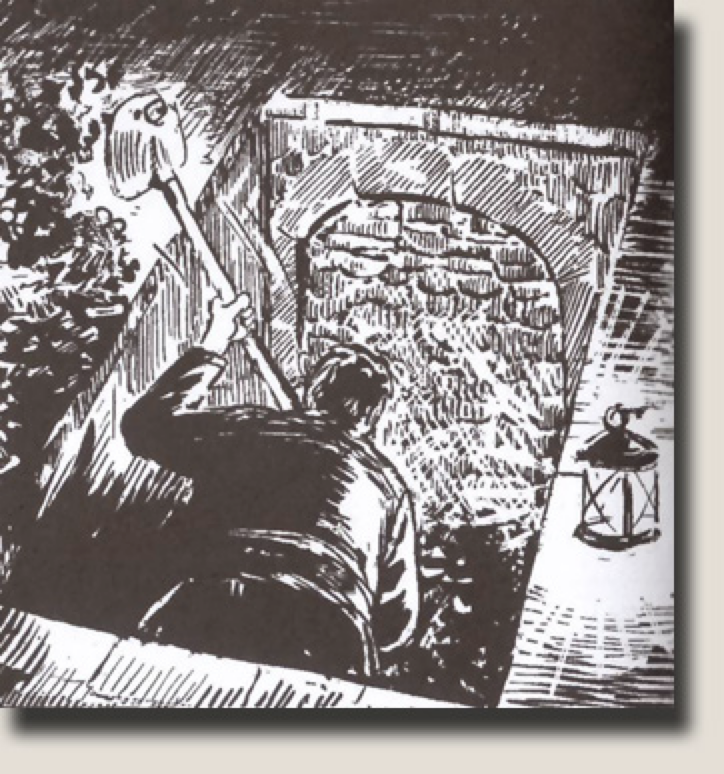

Artistic interpretation of how Saunière may have discovered the Tombeau des Seigneurs

('Le secret de l'abbé Saunière' © Antoine Captier, Marcel Captier and Michel Marrot)

The quest for the crypt from 1956

Already shortly after Saunière's death and certainly after the arrival of Noël Corbu in Rennes-le-Château, there were already stronger rumour's that Saunière had discovered a treasure in his church. The first treasure hunters quickly found their way to Rennes-le-Château to carry out non-archaeological excavations in the church. The first to work on the church floor were Malacan, a doctor from Chalabre, and René Descadeillas, journalist and chief archivist of the library of Carcassonne. They were accompanied by Messrs. Brunon, Busque and Rivals. In the first months of 1956, they found a perforated skull under the floor just before the altar. From that moment on, more and more fortune seekers appeared in the village every year, carrying out excavations, including in and around the church itself. The main names were Noël Corbu himself, the engineer Jacques Cholet, the writer Robert Charroux, Roland Domergue accompanied by a medium and later also Henri Buthion. Especially the Parisian engineer Jacques Cholet achieved the most surprising results in 1959. Cholet later wrote down his findings about his excavations in Rennes-le-Château in the famous Cholet report.

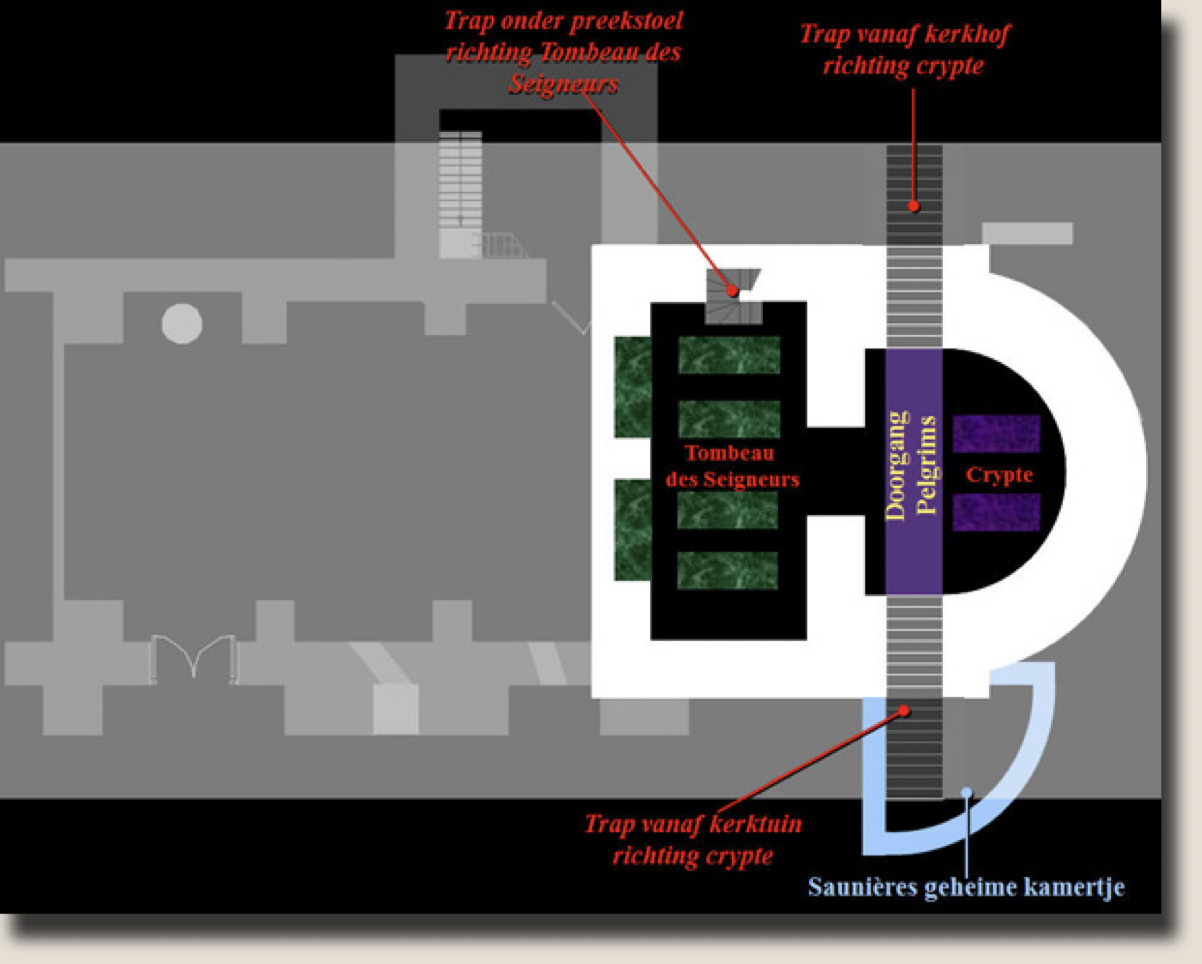

In 2001, Belgian researcher Paul Saussez went over the Cholet report together with notary André Gastou, who was present during Cholet's excavations in the church and recorded his finds. Gastou confirmed that Cholet had indeed discovered a staircase under the pulpit that led to the cemetery and also agreed that he had found a stone arch of a possible doorway in the floor of Saunière's secret room in the church. Cholet thought, like Saussez, that there might be a passage under the church from this location.

The arch of an access to the crypt visible in Saunières secret room, first discovered by Jacques Cholet in 1959. (Photo © Saussez 2002).

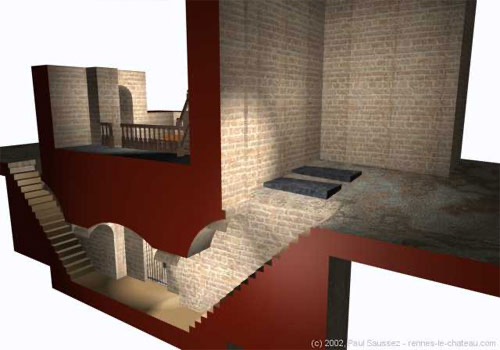

Saussez - His reconstruction of the possible stairway near the secret room.

However, Cholet did not investigate the case further. Others, such as Gérard de Sède, claim that this was because strangers had placed a 'boobytrap' in the church with a heavy support beam, with Cholet barely escaping death. Cholet then left the village headlong to never return. However, this story is not a fable because several people could testify to it. Probably certain villagers could not really stomach the Parisian. However, Cholet ... was later seen back in the village to assist Roland Domergue in his excavations, among other things. Cholet had probably stopped previous excavations because he was at the end of his money to finance further excavations. It is clear that from 1891 Saunière had the church garden and the cemetery closed to keep snoopers out. In addition, in January 1892, he had the secret room next to the sacristy at the church erected to be able to dig to the possible pilgrim passage that led to the crypt. On the other hand, the pilgrim's passage [that possibly] led to the cemetery, where Saunière began digging heavily in 1895 in search of the second entrance (Saussez 2004).

The entrance to the Tombeau des Seigneurs and the pilgrim passage to the crypt from the cemetery and the church garden (Photo © Paul Saussez 2004).

Professor Eisenman's professional soil research

In the early years of the 21st century, Rennes-le-Château was in the news when the renowned American professor Robert Eisenman of California State University and his team were consulted to conduct high-tech soil research in the church of Rennes-le-Château and Tour Magdala. Robert Eisenman is best known for his groundbreaking work on the Dead Sea Scrolls and was consulted by the city council of Rennes-le-Château through Michael Baigent. This co-author of The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail had assisted Eisenman in the early 1990s with ground radar research in Qumran (Saussez 2011).

The American professor Robert Eisenman of California State University (Photo © Le trésor du curé - Envoyé Spécial 2003).

In April 2001, Eisenman's American team performed the first ground radar scans in the church and Tour Magdala. The scans showed two anomalies under the floor of the nave of the church that were no deeper than 60 cm. Probably these were banal remains of Saunière's restoration works or the debris of treasure hunters like Cholet in the 1950s and 1960s (Saussez 2011). A soil scan in Tour Magdala also brought a rectangular object to light. It was the latter that caused a lot of speculation in the media; it was assumed that this might be a hidden suitcase from Saunière (Saussez 2011). While the soil scans in the church were continued in March 2002 by Eisenman's team, a request was submitted to the local authorities to carry out an archaeological excavation.

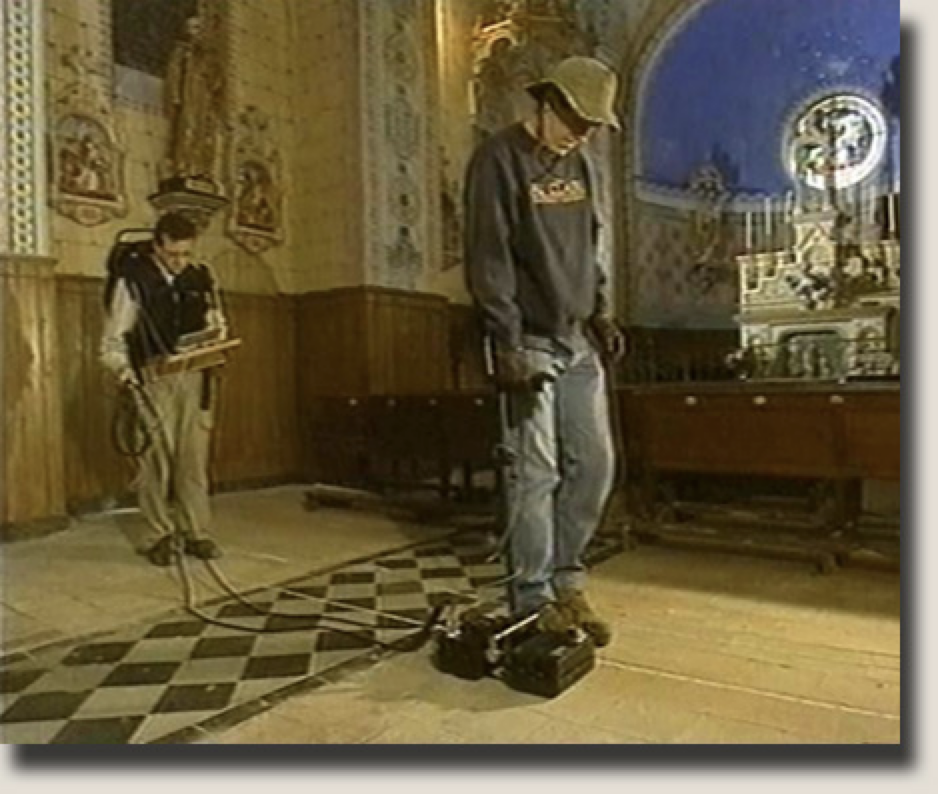

Soil research carried out in March 2002 by the American team of Professor Robert Eisenman. (Photo © Le trésor du curé - Envoyé Spécial 2003)

At the time of that soil investigation, the Belgian architect and researcher Paul Saussez, an expert on the crypt, was present. He noted that ground scans were carried out in places in the church, including in the nave, where there was little chance of finding traces of a crypt. He also saw that the scientists' portable measuring devices were only adjusted to receive ground echoes up to 1.5 m (Saussez 2011). Saussez then gave them the advice to work in the apse of the church where the altar is located and where a crypt can normally be found. He also asked them to adjust their equipment to a depth of 5 m (Saussez 2011). Meanwhile, the excavation request of Eisenman's team was rejected by the Comité Inter-Régional d'Archéologie (CIRA) that deals with such archaeological requests.

However, at any cost, the local city council under the leadership of the then dubious mayor Jean-François Lhuillier wanted to carry out excavations under the Tour Magdala where they wanted to find the hidden (treasure) chest of Saunière. In August 2003, a municipal worker was allowed to bring the case to the mayor, Professor Eisenman, Michael Baigent and an army of journalists. Great was their disappointment when some time later Saunière's alleged suitcase turned out to be just a rectangular piece of boulder (Saussez 2011)!

The soil survey results - Confirmation of Saussez's suspicionsI

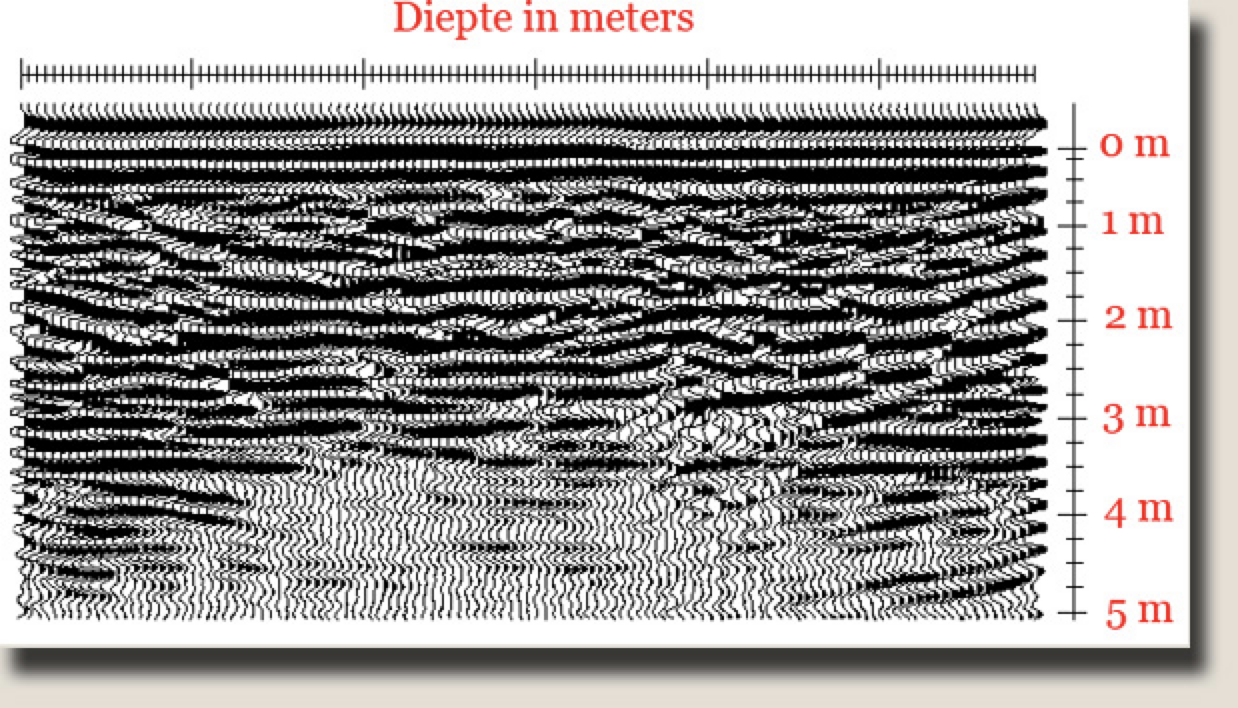

It was not until September 2003 that Professor Eisenman showed the results of the ground radar scans at the annual meeting of a geographical association in Wisconsin. However, the measurement results of the scans in the apse, which were performed on the advice of Paul Saussez, were not shown (Saussez 2011). However, Saussez filed a request to obtain a copy of Eisenman's ground radar results. Finally, after 20 months of waiting, Saussez got his hands on them in May 2005. The long wait had been worth it because the ground scans showed that there was an underground cavity at a depth of 5 meters under the apse of the church, exactly as Saussez had predicted (Saussez 2011).

Eisenman's soil scans clearly show the cavity under the apse at a depth of 5 m: The crypt does exist! (Photo © Eisenman & Saussez 2002-2005)

The soil research results were confirmed by a second independent research team. In April 2008, British businessman Sir Richard Heygate asked the city council of Rennes-le-Château to conduct ground radar research in turn. On May 7, 2008, he received permission and the church floor was completely scanned. Results were again not released and the minutes of the city council meeting were also silent.

The British businessman Sir Richard Heygate (Photo © www.bartandbounder.com)

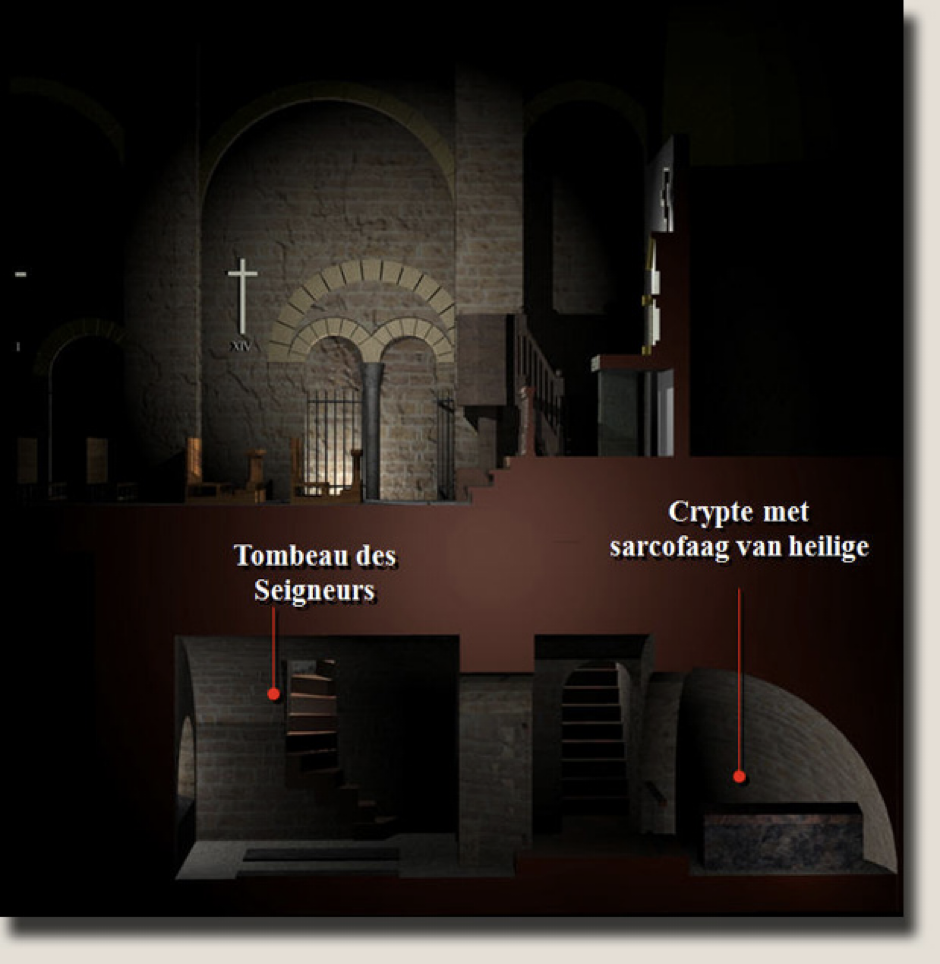

Through people involved, Saussez managed to gather information about the research results carried out by Sir Richard Heygate's team. The existence of the cavity under the apse was once again confirmed and a second room was also found under the nave of the church. Both rooms, the Tombeau des Seigneurs and the crypt, would be connected via a narrow passage. Moreover, an 'indefinite mass' would have been observed in space below the apse, which could possibly indicate a sarcophagus of the saint.

CGI representation of the Tombeau des Seigneurs and the crypt with sarcophagus under the church of Rennes-le-Château, designed by architect Paul Saussez (Photo © Paul Saussez 2004)

Recent developments in 2011

Currently, Paul Saussez is carefully preparing an extensive dossier to convince certain agencies such as La Direction Régionale des Affaires Culturelles Languedoc-Roussillon (DRAC) to carry out archaeological excavations. In the past, the reaction of the DRAC was always negative because, according to them, there were no well-founded reasons for such an excavation and that is why they did not give permission to Professor Eisenman's team, among others. Saussez will also look for the suitable archaeologist for the job and will also try to raise funds to finance this project. Let us all hope that in the future Paul Saussez will receive the green light from the authorities involved so that the year 2012, through the discoveries in the crypt, can enter the Rennes-le-Château annals in a positive way to overshadow the retarded ideas of doomists and light-minded people in connection with Mount Bugarach.

Special thanks to M. Paul Saussez who allowed me to quote from his works, generously offered me his personal stories and information and gave me permission to use the images from his CD-ROM.

Great thanks also to Monsieur Patrick Mensior for giving me permission to paraphrase some fragments of his article "L'état de l'église de Rennes-le-Château in 1808!" dans son bulletin Parle-moi de Rennes-le-Château 2010.

*************************************************************************