The report of the Saglio Commission (1911)

The material is distributed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 license. From Mariano Tomatis.

With many thanks for Mariano in giving me permission to reproduce his excellent researches!

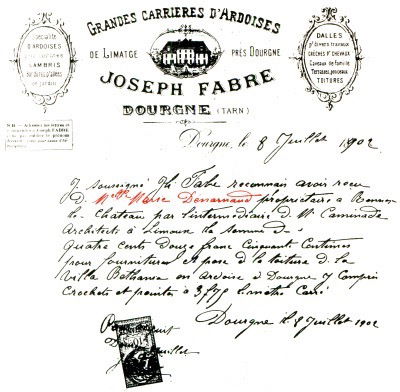

With the declaration of the various expenses by Saunière, the Saglio Commission has all the elements to judge the situation and to give a complete report to the Bishop. It is during a more in-depth review of the 61 invoices that an element that was first ignored comes to light: this is the header of invoice 58.

Issued by Joseph Fabre, the invoice is strangely in the name of Marie Denarnaud. Combined with Saunière's claim that he does not own the land on which the villa, the Tour and the gardens were built, that document is the most obvious clue that much of the money was spent on building a series of architectural works that the priest is no longer in possession of.

The Commission's report is delivered into the hands of Monsignor Beuvain de Beauséjour on 4 October 1911; the report opens with a rather merciless summary of the situation:

Report of the commission instructed by Monsignor the Bishop to examine the accounts of Mr. Saunière.

Monsignor, we have the honour to explain to you that, having entered into a relationship with Mr. Saunière to examine his accounts as you had instructed us to do following the judgment of the ecclesiastical court, we could not get him to present us with any accounting, no matter how rudimentary it was. As far as revenue is being considered, he merely pointed out to us the different sources he had already presented at the trial and which are simple statements without any evidence and among which some of them appear to be far-fetched. It is so, for example, that he attributes a gain of three hundred francs a month in the factories of Espéraza to the family that hosted him, when it would be easy to show that on average this does not exceed half of that amount.1

The suspicions about the revenue have therefore remained. It is clear to the Commission that Saunière is inflating some figures to hide other unjustifiable revenue. The outputs are equally dubious and supported by documentation for only 36 thousand francs: For the exits, he presented a package of invoices, some regularly paid, others constituting simple expense reports, but the total of the sums entered on these sheets only amounts to about 36,000 francs; by us, invited to present an expense account that reached the overall figure of 193,000 francs that he himself had indicated during the process, he presented us as for the revenue an approximate account that consists simply of a numbering of seven items corresponding to figures that are not justified by anything. The Commission goes on to point out the attitude held by Saunière throughout the exchange of letters: it seemed more important to him to underline the fact that he had never incurred debts or spent more than he could have, when in reality the General Court simply wanted to verify the accounts and the expenses made: Mr. Saunière, moreover, always made it clear that it was important for him only to prove that he had not incurred debts, when it was instead his own accounting that had been challenged to him. He did not agree to come and meet us to provide us with oral explanations, pretexting the need to avoid any emotion in which his state of health puts him, and we did not believe that he had to take us to Rennes predicting the total futility of this passage.

The last part of the letter is the decisive one:

having stated that the land does not belong to him, Saunière implicitly revealed that, excluding the church and the garden of Calvary, the entire domain is not in his possession, and therefore the enormous expense made to raise it went all in favour of a private family and not of the Church.

It will be precisely this point that will cost him the definitive sentence:

We believe that we must report a serious fact to your Greatness: Mr. Saunière recognises that the land is not in his name; therefore, the constructions, following their fate, would not belong to him. All expenses, with the exception of 27,000 francs consecrated to the church and perhaps to the ordeal and 15,000 francs devoted to furniture, according to the statements of Mr. Saunière, therefore go to the benefit of the nominal owner of these lands. On the other hand, certain construction expenses were made on behalf of the Dénarnaud family because, among the documents so incomplete that Mr. Saunière gave us, we found one, dated July 8, 1902 and issued by Joseph Fabre, of Dourgne, who acknowledges having received from Miss Dénarnaud, owner in Rennes, with the mediation of Mr. Caminade, architect in Limoux, a sum of 412.50 francs for the supply and laying of the roof of Villa Béthania.

Once the Commission's documentation has been received, on 13 October 1911 the indictor of the Court of Ecclesiastical Cases Pennavayre drew up a document inviting the Court to summon Saunière for confirmation of the sentence:

Mr. Saunière never made sure to present any accounting, as rudimentary as it might be. He has simply submitted excessively summary calculations and has always refused, despite the benevolent invitations of the committee, to provide the necessary verbal explanations under the pretext of 'the need to avoid any emotion in which his state of health puts him'. Not getting anything, the commission thus had to evaluate Mr. Saunière's accounts: As far as revenue is called: he merely indicated to us the different sources that he had already submitted to the trial and which are mere statements without any evidence and among which some of them appear to be far-fetched. For the outlays: he presented a package of invoices, some regularly paid, others constituting simple expense reports. But the total sums entered on these sheets amount to only about 36,000 francs; by us, invited to present an expense account that reached the overall figure of 193,000 francs that he himself had indicated during the process, he presented us as for revenue an approximate account that consists simply of a numbering of seven articles corresponding to figures that are not justified by anything. Moreover, the committee notes in its report that Mr Saunière has built on land that is not in his name. So the constructions don't belong to him. All expenses, with the exception of 27,000 francs consecrated to the church and perhaps to the ordeal and 15,000 francs devoted to furniture, according to the statements of Mr. Saunière, therefore go to the benefit of the nominal owner of these lands. On the other hand, certain construction expenses were made on behalf of the Dénarnaud family ...All these facts seem to prove: 1) that Mr. Saunière did not submit to the judgment of the Court of Ecclesiastical Cases which condemned him to carry his accounts to Monsignor the Bishop of Carcassonne. 2) that he has used for his own profit or for the profit of third parties considerable sums entrusted to him for pious works and consequently having the character of ecclesiastical goods. For all these reasons, I, the undersigned A. Pennavayre, prosecutor of the Court of Ecclesiastical Cases of the Diocese of Carcassonne, I have the honour of praying to Mr. Official to bring to his court Mr. Abbot Saunière, old curate of Rennes-le-Château.2

The Vicar General, having received Pennavayre's request, with a document of October 30, 1911, establishes the date on which Saunière will have to appear in court:

We quote Mr. Bérenger Saunière, an old curate of Rennes-le-Château, to appear before the Court of Churches of the Bishopric on Tuesday, November 21 of this year at 10 a.m., to be forced, by means of law, to execute the judgment of 5 November 1910. Mr Saunière will have the courtesy to communicate before 9 November the name of the lawyer to whom he he intends to entrust his defense so that the Court can examine him. The court hereby declares that they will not be accepted as prosecutor or defender of Mr. Bérenger Saunière, Mr. Dr. Huguet who pleaded his case in the first trial.3

Saunière is even prevented from being defended by the lawyer who has followed all stages of the trial. On November 4 the priest tries to oppose the summons but a letter of November 9 signed by the Vicar General confirms the date of appearance on November 21. As during the previous year's trial, Saunière also deserts the room on this occasion. Having noted his absence, on November 21 the Vicar General draws up a document in which, taking note of the absence of the priest, he moves the date of appearance to December 5, 1911:

Considering that the fixed day and time Mr. Bérenger Saunière did not show up either in person or through a prosecutor, with those present, we peremporibly quote Mr. Bérenger Saunière to appear before the court of ecclesiastical cases in the bishopric on Tuesday, December 5, 1911 at 10 a.m. to be forced through the means of entitlement to the execution of the judgment of November 5, 1910. In the absence of a response to this injunction he will be declared in absentia and judged as such.4

1. Transcribed in Jacques Rivière, Le fabuleux trésor de Rennes-le-Château, Bélisane, Nice 1983, pp. 236-237 here translated by Advent Child.

2. Transcribed in Rivière 1983, pp. 239-241 here translated by Advent Child.

3. Transcribed in Rivière 1983, pp. 238-239 here translated by Advent Child.

4. Transcribed in Rivière 1983, pp. 242-243 here translated by Advent Child.