The request for clarification (1911)

The material is distributed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 license. From Mariano Tomatis.

With many thanks for Mariano in giving me permission to reproduce his excellent researches!

The final report of the Saglio1 Commission presents the revenue and expenditure in two separate points. The first are derived from the list in 26 points provided by Saunière, the second are reported from the calculations made on the 61 invoices:

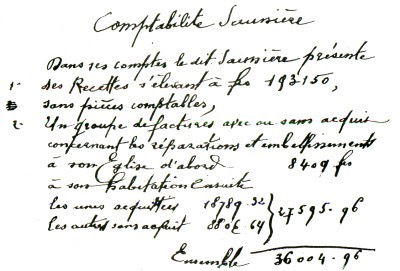

Saunière's accounts

In his accounts, the aforementioned Saunière presented:

1st Of the expenses amounting to 193150 francs without accounting documents,

2° A group of invoices, paid and unpaid, concerning repair and embellishment of his Church for an ammount of 8409 francs and later for his home those paid for 18789.32 francs, the other unpaid for CHF 8806,64 [total of the last two:] 27595,96. In total: 36004.96 francs.

The total expenditure is not excessively far from the 36250.01 francs that are obtained by correcting the various mistakes made. The biggest difference is to the detriment of Saunière: according to the Commission, in fact, only 8409 out of 36004.96 francs (equivalent to 23.4%) were spent on ecclesiastical goods; in reality the correct calculation (11585.84 out of 36250.01) leads to a percentage of 32%. The first analysis ends on March 19, 1911, and the Commission writes a letter to Saunière2 asking him to better specify some obscure points related to the list of revenues provided; point 2 ("Hosted family that earned 300 F per month for 20 years" for 52,000 francs) is not convincing: the priest is invited to provide an explanation of these somewhat too high figures. In fact, in 1885 Saunière earned 75 francs a month, and the allocation of 300 francs per month to workers in a hat factory is actually excessive. To this first point Saunière responds:

Twenty years ago, I took with me a family of father, mother and two children. The father and mother earned 300 francs a month. Our income was common cash. Hence savings of 52,000 francs. The family worked in the hat business.

With regard to point 15 ('Alms, an average of 1200 francs a year for 15 years' for 18,000 francs), the Commission seems to have made excessive the amount indicated, and they find it strange that the priest has never kept a notebook to keep a note of it. Saunière makes the point better:

The alms box was intended for visitors who, after listening to my explanations about Rennes and accepting my courtesies, rewarded me with an offer that, in practice, was a tipping. Since the bathers of Rennes-les-Bains were numerous, this explains their generosity.

The Commission wants to know the date on which the lottery indicated in point 16 was organised, and Saunière replies:

The lottery took place around 1887.

The most suspicious figures are, of course, the anonymous ones – among other things very high: the Commission mentions the 25 thousand francs in point 3, the 20 thousand francs in point 14 and the 30 thousand in the 17th point. While not explicitly asking for the names of donors, Saunière is expected to provide at least the dates on which such donations took place. The answer eludes the request, limiting himself to reconfirming the role of his brother:

My brother, being a preacher, had a lot of knowledge. He acted as an intermediary for these donations. The Commission also considers the rumours concerning postcards (paragraph 18), stamps (paragraph 19) and copies of letters (paragraph 20) strange: does it mean that Saunière had a trade in items of that kind from which he could make a profit? The priest responds:

The postcards are from the area of Rennes-le-Château. There are 31 of them. All bathers take the complete collection, that is, 3.10 francs each. These postcards are so successful that I have to stock up on them. These postcards are new and my property. My collection of old stamps amounts to 100,000. It is complete and, for sale, I comply with the current prices. Fans, very happy to turn to me, never bargain on the price.

At the request to make the entry relating to the advertisements for newspapers and flyers better explicit, Saunière writes:

I have some young people make the ads for newspapers and flyers. They are satisfied with the price I offer and I still make a profit from it.

The Commission also wants to know the origin of the antique furniture and other objects mentioned by Saunière in paragraph 22, and the priest replies:

Antique furniture, ceramics and fabrics are purchases I made in the region. Their sale compensates for the costs incurred by me and my travel.

As a final request, the Commission asks Saunière to keep the last two sums in the assets, referred to in paragraphs 25 and 26. Saunière responds like this:

Why shouldn't I include free transport and my personal work in the assets? Aren't they a real savings for me?

All these answers are sent by the priest in a letter dated March 25, 19113. The canon Charpentier replies on April 4, 1911 that he was not yet satisfied with the explanations provided, complaining about the vagueness used by Saunière in answering:

Allow us to tell you our astonishment by seeing you answer in such an incomplete way and to which we are used to the questions we asked you. In particular1. We asked you on which bill accounts or accounts you based to claim an annual and regular collection of 1200 Francs from the alms box and we asked you to let us know. You didn't answer.2 We asked you the dates on which the most important donations were made to you through your brother. (art. 3 – art. 1 – art. 17). You didn't even answer. We have started the verification of the expense accounts; it is not a statement, it is a series of supporting pieces and they are moreover incomplete, since the total sums they mention amounts to about 36000 francs, when even you yourself have recognized an expense of about 20,000 francs; you do not mention any expense for the purchase of land, no expense can be related to very large constructions and construction works to which you have given yourself; it is absolutely necessary that between now and the end of the week you send us a true statement where you will give us the details of the total expense and not only that of a small part of your exposure4

On 8 April 1911, Saunière regrets that he did not explain himself sufficiently in the previous letter, and responds to the various points raised. Speaking of alms, he explains that he indicated the average income precisely because he had never taken note of the exact figures:

I have repeatedly told visitors about the story of Rennes-le-Château to visitors, and since they were people belonging to high society, they left in the offering box tips that they would not dare to give in their "cicero" in their hands.5

As for the gifts he had through his brother Alfred, Bérenger specifies a period of time from 1895 to 1903. On the lack of notes about the purchase of the land and the works to carry out the various construction works, the priest justifies himself by explaining that the request that had been addressed to him said nothing about these points, and that moreover the land had been purchased by the family he hosted. Regarding the lack of precision used to answer, Saunière answers categorically:

I would like to point out that I am neither a trader nor an entrepreneur. For this reason I acted responsibly and in my operations I allowed myself to be guided by the funds I had, believing it superfluous to keep an accounting book that would be agreed rather to an industrialist intent on manoeuvring the money of a bank. I limited myself to a few notes that were enough to make me avoid missteps and avoid disasters.6

The priest also defends himself against the defamation brought by someone against him on the pages of Les Veillés des Chaumières, which he defines as "an announcement to which I was totally foreign"; following the article published in La Semaine Religieuse de Carcassonne, written without even summoning him to clarify the case:

if I had not been a priest first of all, I would have asked the civil court for a reparation that he would certainly have granted me. I preferred to be silent and suffer, preferring to wait from Rome a repair that I trust will be granted to me.7

About the spiritual exercises, Saunière points out that if his request had been accepted by the Grand Seminary of Carcassonne, he would have already presented himself:

I count on attending them as soon as possible. I allow myself to believe that the diocesan administration will be able to see in this gesture a proof of my docility and my priestly spirit.8 Saunière sends the letter to Vicar General Cantegril, unaware that the case has passed into the hands of the Bishop. In a letter dated 19 April 19119, the Commission of Inquiry informed him that from now on it will have to address all communications to Monsignor Beuvain de Beauséjour, and that it would be easier if he came in person to discuss the matter face-to-face. On April 24, 1911 Saunière began the spiritual exercises in Prouille10: during his stay he wrote another letter that he addressed again to the Vicar General, denouncing poor health conditions and heart problems that would prevent him from presenting himself personally to the bishop: he prefers to continue the communications by letter. After 10 days, on May 6 the priest sends the certificate of attendance to the Vicar General11. On 9 May 1911, the Commission renewed the request for a more precise list of expenses, since there is such a big difference between the documents delivered (which indicate just 36 thousand francs of expenditure) and the list of revenue received (which exceeds 190 thousand francs).

In case you have really lost the invoices, you must ask for a copy from the person who carried out the work at the domain, thus reconstituting a more complete and exhaustive documentation12.

On 14 May 1911 Saunière confirmed his precarious state of health, without responding to the point raised by the request of the Commission13, which then returned to office on 27 May complaining precisely of the too vague answer:

Your letter of May 14th responds to only one of the points we touched on in the one we sent you on May 9. Please refer to that letter and clearly answer the questions we have asked you in a very precise way and tell us if you are willing to help us rebuild your accounting.14

On June 2, Saunière resumes the old arguments about the impossibility of providing any duplicate of invoices: his accounting was not scheduled in advance, he evaluated day by day the amounts to be spent and finds it absurd to ask the old suppliers for a second proof of the expenses made; he repeats that the requests addressed to him would be more suitable for a trader than for a priest, and he threatens to make known to Rome – through his lawyer – the incorrect attitude of the Court15. The Commission is not there, and on 14 June it renews its request to respond to the request made on 9 May:

Since you have spent about 200 thousand francs and have provided an explanation for only 36 thousand, please indicate the other expenses and try to provide, as much as you can, the documentation.16

On June 20, Saunière faces the various points raised one by one, while maintaining a vague tone:

Referring to your letter of May 9, I find these general indications:

1st apply to major suppliers for a duplicate of their invoices.

2nd report the cost of the land purchased

3rd to let you have the amount of my taxes.17

At the first request he replies that he has no intention of exposing himself with a request for duplicates that would reveal to suppliers suspicion or distrust of him. Speaking of the land, he repeats what has already been said in the past: they were purchased by the family he hosts, and the expense was borne by her. To the request relating to taxes, the priest states that the only one relating to the rent of the presbytery, and to prove this he attaches to the letter a sheet that testifies to the amount. The letter continues with a series of complaints: his attitude has always been correct, he has always provided all the data that was requested of him and despite everything he is still asked to produce new supporting material. He is currently recovering after 15 days in bed, and is waiting for a response from Rome in which he puts all his trust. The Saglio Commission is still not satisfied with the answers and is demanding greater precision. By a letter on July 7, 1911 they asked him:

1. How much did it cost you to buy the land?

2. How much did you roughly spend on the restoration of the church and the ordeal?

3. What sums were used for the construction of the Bethania villa, the Magdala Tour, the adjacent terrace and the two gardens?

4. How much did the interior decoration and furniture cost approximately?

We absolutely need these indications before closing our relationship, and since you claim that you cannot provide the accounting, give us at least approximate figures.18

Saunière decides that it is time to turn the endless exchange of letters: having denounced gains of 193 thousand francs, he is forced to respond to the last letter by appropriately distributing the figures in order to obtain an expense equal to the revenue. The letter was sent by the priest on July 14, 1911:

Monsignor Vicar General,

Eager to answer as exactly as possible the various questions you are asking me, I took a few days to realise the sums devoted to the different work I had carried out.

| 1. | Purchase of land – I believe that have to remind you that they don't they were purchased in my name | 1,550 |

| 2. | Restoration of the Church | 16,200 |

| Calvary | 11,200 | |

| 3. | Construction of Villa Béthania | 90,000 |

| Magdala Tower | 40,000 | |

| Terrace and gardens | 19,050 | |

| Internal adaptation | 5,000 | |

| Furniture | 10,000 | |

| 193,000 | ||

I hope that this little information will allow me to close a deal that has earned me so many reminders and has strongly involved me in recent months.

A summary analysis of the figures reveals the extreme confusion of Saunière, who in addition to the strange figures provided in the revenue list, is unable to provide certain and documented elements even of expenses (many of which relate to goods unrelated to construction and decoration works),

1. Reproduced in Jacques Rivière, Le fabuleux trésor de Rennes-le-Château, Bélisane, Nizza 1983, p. 176.

2. Transcribed in Rivière 1983, p. 222.

3. Reproduced in Rivière 1983, pp. 211-213.

4. Transcribed in Rivière 1983, p. 214 here translated by Lucia Zemiti.

5. Reproduced in Rivière 1983, pp. 215-220.

6. Ibidem.

7. Reproduced in Rivière 1983, pp. 215-220.

8. Ibidem.

9. Transcribed in Rivière 1983, p. 221.

10. Correspondance de Bérenger Saunière (1896-1915), April 24, 1911.

11. Carnet 2004, 6 May 1911.

12. Transcribed in Rivière 1983, p. 224.

13. Reproduced in Rivière 1983, pp. 225-226.

14. Transcribed in Rivière 1983, p. 227.

15. Letter reproduced in Rivière 1983, pp. 228-230.

16. Transcribed in Rivière 1983, p. 231.

17. Reproduced in Rivière 1983, p. 232-234.

18. Transcribed in Rivière 1983, p. 235.

19. Reproduced in Rivière 1983, p. 126 here in the Italian translation of Advent Child.